UNCANNY: The Young Woman Who Invented Frankenstein

What if the credit for the entire genre of science fiction belongs to an 18 year old woman?

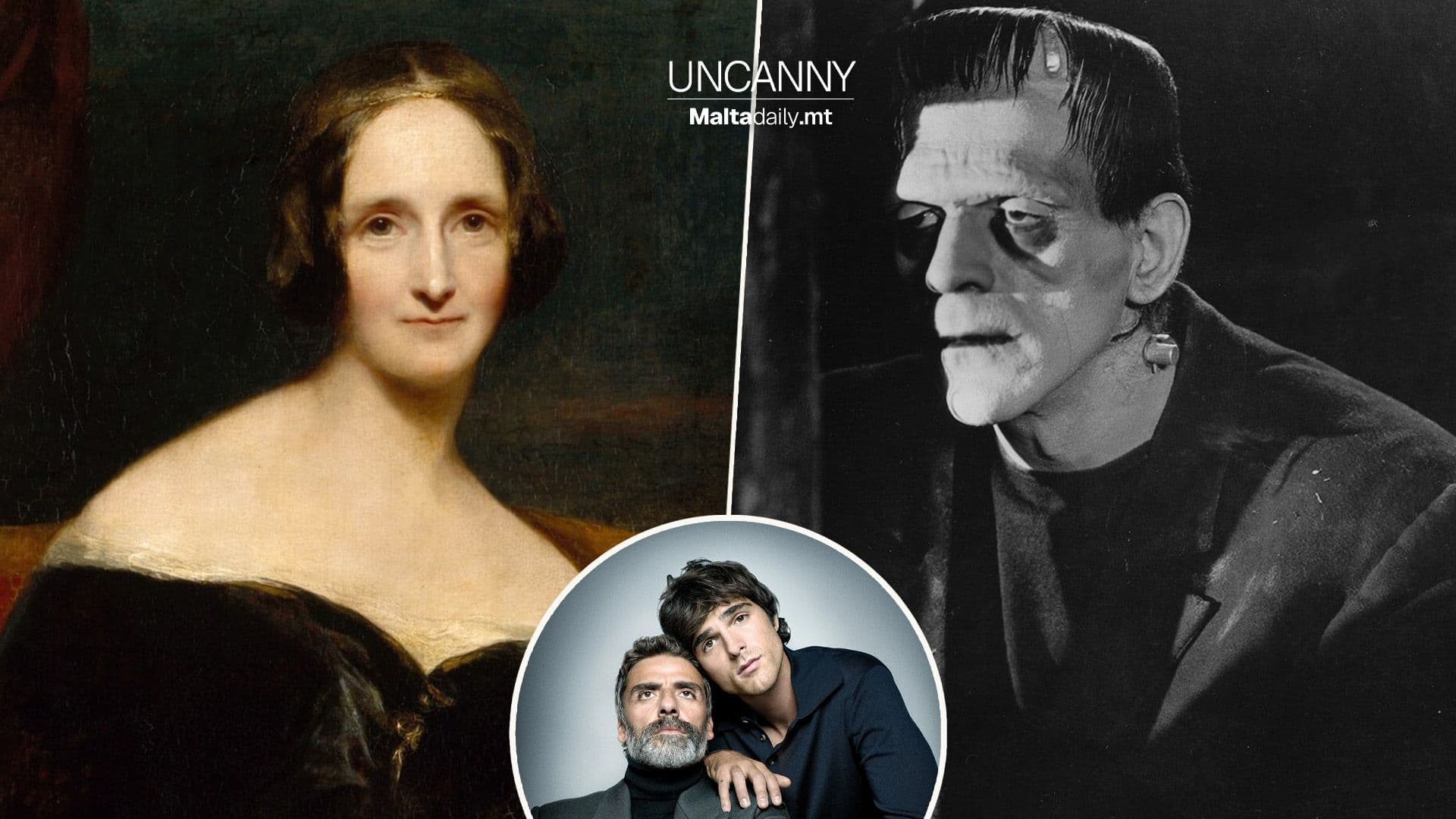

As Netflix prepares to release Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein’ (starring Jacob Elordi & Oscar Isaac) this spooky season…

It’s only fair that we shed light on the mind behind it all; Mary Shelley. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was born on 30th August 1797 in London to a family of radicals, writers and thinkers.

Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, wrote one of the first seminal feminist texts, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Her father, William Godwin, was also a renowned radical philosopher and writer. Her family was not the only link she had to books, debate and revolution.

At just 16, she met the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. He was already married by then, but this didn’t stop their relationship. They ran away together to Europe, and, in 1816, she found herself in Switzerland… which is where our story really begins.

There they stayed with other poets Lord Byron (with his own links to Malta *wink*) and John Polidori (who published the first modern vampire story). One stormy night, Byron proposed a challenge: ‘Let’s write a ghost story.’ At first, Mary struggled to come up with a concept, but that night she had a nightmare.

She dreamt of a scientist who was terrified of the life he had created. Thus, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, was born. Mary was just 18 when she started the book and finished it at 19. It was so good that it allegedly won the contest, surpassing two of the greatest literary minds of her day.

When Frankenstein was first published in 1818, it was anonymous. A woman coming up with such dark brilliance was unthinkable back then. Her name appeared for the first time in the 1821 edition, kicking off a long career. But what is Frankenstein about? Very often we see this dumb lumbering giant of a zombie being chased by mobs holding pitchforks and torches.

In Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, the monster was not dumb at all. His creator, Victor Frankenstein, wanted to create life out of raw, dead material. Upon creating his monster however, he was horrified at his creation. The themes start to pop immediately: this is a story about playing God. It is a critique of Enlightenment rationalism but also of religious notions of humanity.

The monster learns to speak and read fluently, quoting Paradise Lost. That last epic poem by John Milton (1608-1674) retells the story of Satan, his expulsion from heaven and the temptation of Adam and Eve.

This is why Frankenstein was originally called ‘The Modern Prometheus’, a reference to the Titan in Greek Myth who steals fire from the gods to give to humanity. The book then recounts how Frankenstein deals with the horror of his creation, the request by the monster to have a wife created for him, and the worldwide chase that leads to the Arctic. It is a philosophical exploration on the nature of humanity and its achievements… and how it can go awfully wrong.

So where did this idea of a big green monster come from? Well, we need to look at drama and cinema. In 1823, the play ‘Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein’ portrayed him as a silent, lumbering figure. Already, the creature lost its voice, both literally and symbolically. Audiences preferred the visual drama rather the complex moral themes.

Then, in 1931, James Whale adapted the story into film, starring Boris Karloff as the now iconic monster. The film emphasised the horror element, with Karloff’s monster having the iconic flat head, bolts screwed into his skull and groaning, zombie-like mannerisms.

After that, Frankenstein’s monster (now often mistakenly given the name of his creator) became a classic monster alongside Dracula, the werewolf, the mummy, etc. Del Toro’s upcoming adaption seems to be challenging this caricature, promising a more faithful adaptation of Shelley’s work. As aforementioned, the book explores important themes. One of them is the interplay between nature and science.

Like Prometheus, Victor Frankenstein is responsible for god-like power but is tormented by his realisation. He abandons the monster, bringing to light another theme: a creator that abandons his creation (a notable critique of religion).

So long before H. G. Wells popularised time travel in his 1895 ‘The Time Machine’, or Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ saga explored themes of interstellar warfare… One young woman set the standard for science fiction, the themes explored within it and gave us one of horror’s most iconic figures.

#MaltaDaily